7 ways business can be agents for peace

Article published on WEF website on 05/28/2019 by Victoria Crawford

The last decade has shown a steady decline in the level of peace around the world, as civil wars, terrorism and rising violence become increasingly prominent. The costs of this are huge, with the impact of violence on the global economy calculated as equivalent to $1,988 per person, or 12.4% of global GDP.

These costs disproportionately affect the poor. The poor are more likely to be affected by conflict in the first place; by 2030, nearly half of the world’s poor are expected to live in conflict-affected situations. Conflict also serves to further entrench economic development challenges. In the 10 most conflict-affected countries, GDP is held back by violence by between 30% and 68%.

We need to break out of this cycle.

Recent research by the UN and the World Bank points to an urgent need for the international community to refocus on building peaceful societies and preventing violent conflict, which they calculate could save between $5 billion and $70 billion per year.

Business, alongside all stakeholder groups, has a key role to play here, but all too often their involvement in building peace is little more than an afterthought. This needs to change. So what can business do to contribute to peace?

1) Explore new places

Concerns about security risk, costs and reputation mean that companies often overlook business opportunities in conflict-affected areas, even in cases where this might be feasible. This leads to a vacuum of well-governed businesses operating in fragile regions.

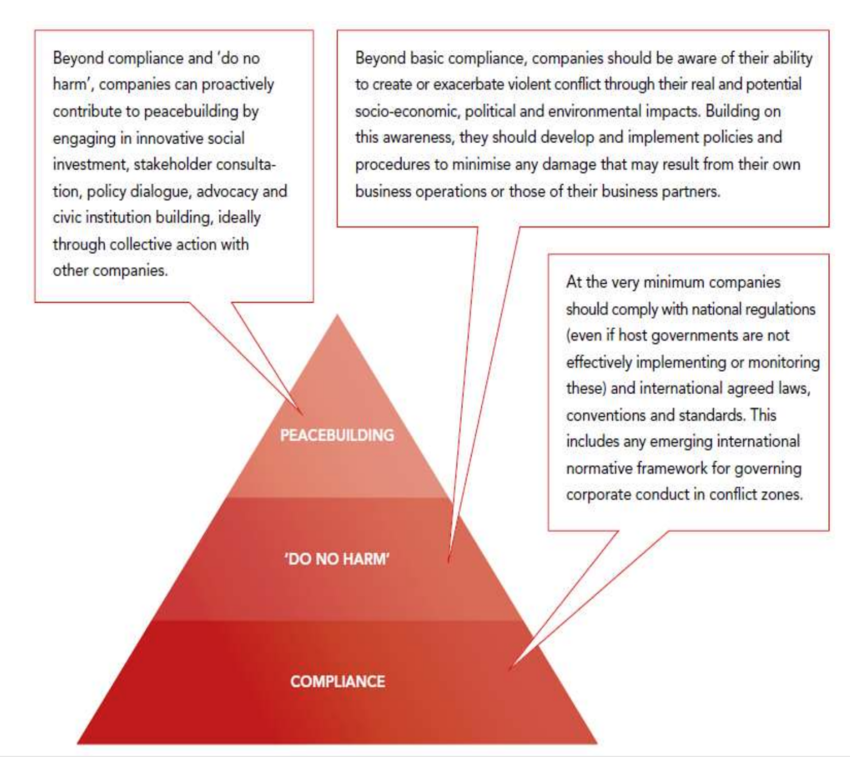

Business presence in itself is no guarantee of a positive contribution to peacebuilding. There are plenty of examples of businesses, even those that are well-meaning, exacerbating conflict; and it is essential that businesses operating in such environments adopt conflict-sensitive practices.

However, working carefully with development, humanitarian and peace actors to better understand situations on the ground, would enable industry to explore opportunities that also have the potential to contribute to stable and prosperous societies.

Nespresso’s efforts to bring Colombian coffee to international markets, following five decades of conflict, highlights some of the benefits. After the peace deal was signed in 2016, they began sourcing coffee from Caqueta Department, one of the areas most affected by the conflict. By working closely with farmers, they strengthened both the coffee supply chain, providing their business with niche, high quality coffees, and the resilience of the local communities.

2) Measure influence on peacebuilding

Understanding how a business influences peacebuilding is central to improving it. The PeaceNexus Foundation, with support from Covalence, recently launched a Peacebuilding Business Index, which incorporates broader Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) indicators, with additional emphasis on how companies address specific challenges in fragile contexts, such as the disrespect for human rights, high levels of corruption, or the lack of public services.

The criteria used give companies a yardstick to measure and showcase how their policies and practices can actively contribute to the stabilisation and rehabilitation of conflict-affected areas, going beyond simply “doing no harm”, which previous frameworks such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights have often focused on.

Interestingly, the companies that rated well in the index performed financially better than average. It may be that “conflict-sensitivity” serves as a proxy for sophisticated risk management, capacity to adapt and innovate, and the ability to effectively resist “shock-tests” – key factors of financial success.

3) Hire across societal lines

Businesses can reduce, or exacerbate, tensions through their employment processes. Not only can the creation of local jobs address unemployment, often one of the drivers of conflict, but hiring different groups to work together can build good relations between communities. On the other hand, benefiting one group over another in your hiring processes can build resentment, aggravating existing tensions.

An example comes from Datu Paglas municipality in Mindanao in the Philippines, characterised for decades by frequent armed robberies, shootings and ambushes. When local leader Toto Paglas set up La Frutera banana plantation in 1996, he recognised the region’s conflicts, rooted in religious and socio-economic grievances, were exacerbated when Christians were hired in higher-ranking positions than Muslims.

By also employing Muslims as supervisors, including a former combatant as the most senior supervisor, and instituting practices to help communities overcome suspicions and enmity, he facilitated improved relations in both the workplace and the wider community, central to the municipality’s transformation.

4) Put your money where your mouth is

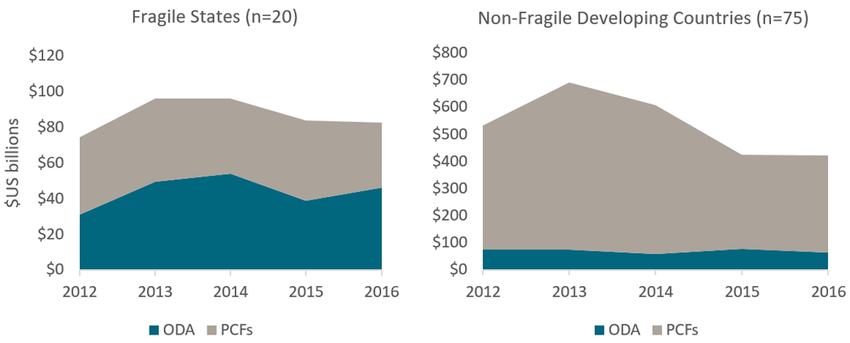

Investment has a vital role in addressing the underlying causes of conflict and fragility, yet investors often shy away from the places that need it most. Whereas private capital makes up the vast majority of external funding to non-fragile developing countries, fragile states remain much more heavily dependent on aid.

There are, however, examples that show that investing for peace is quite possible, and that give an indication of how others might follow suit.

The Cadmos Peace Investment Fund is a global equity engagement fund with a portfolio of 30-50 multinational companies active in fragile countries, selected using both economic and peacebuilding criteria. The International Finance Corporation, the private sector arm of the World Bank Group, has identified seven key principles to engaging the private sector in fragile states, based on academic research and their experiences as they work towards the target of investing 40% of their portfolio in the poorest and most fragile countries.

It is key to identify the right partners to work with, who can help investors reduce risk, by covering first-loss or providing guarantees, or by contributing their skills, expertise and understanding of the context.

A High-Level Group on Humanitarian Investing, recently launched by the World Economic Forum, the World Bank and the International Committee of the Red Cross, brings together representatives from the investor, corporate, humanitarian and development communities to explore this further, unlocking new capital in fragile contexts.

5) Pay your taxes

A glance at history, and the way the state formed in medieval Britain and other Western countries, shows that an effective tax system can contribute to peacebuilding, improved governance, and political and economic stability.

Not only does a well-designed tax system generate sufficient and predictable revenue for states to operate, but it also builds political accountability, enhancing the state’s legitimacy and improving relations between state and society.

This can be seen clearly in Somaliland, formed following the collapse of Somalia in 1991, where the emergence of a democratic government has been attributed to the government’s dependency on tax revenues, which provided those outside the government with leverage to demand inclusive, representative and accountable political institutions.

Business are not the only players here; the feedback loop between the tax system and political accountability relies heavily on citizen engagement as well. However, if businesses, in particular large international businesses, are seen to avoid paying their share, it risks leaving citizens with a sense that the system is inherently unfair. We need a private sector that supports the strengthening of institutions and the rule of law, not one that detracts from it.

6) Share information

Businesses often have a wealth of information about the security, economic and social dynamics of the environments in which they operate, which is frequently kept private as it is considered politically sensitive. However, sharing this information can be valuable for peace, for example disclosing risk assessments with national governments or other relevant national actors can empower them to mitigate tensions and prevent violence.

On the other hand, the absence of information about key aspects of industry can exacerbate conflict. Business can address this by showing leadership on transparency and driving forward transparency initiatives. For example, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) sets a standard for sharing information regarding contracts, production, revenue collection and allocation, and social and economic spending in the extractive industries, overseen by a multi-stakeholder group in each country.

7) Use your voice

The private sector has incredible power to influence the thinking of both government and wider society, and can exert its influence to advocate for peace and support mediation efforts.

An example comes from Northern Ireland, where local business served as both a think tank and a lobbying organisation in the peace process. During the Troubles in 1994, the Northern Ireland Confederation of Business Industry (CBI) published a “peace dividend paper,” laying out the economic rationale for peace, which was picked up by the media, and gave a new momentum to the peace process.

Two years later, the CBI joined forces with other business and trade associations to form the Group of Seven to lobby for peace through discussions with political parties, media statements and individual appeals. As the Group’s former Chairman, the late Sir George Quigley noted, while business cannot build peace alone, the pressure they exerted “made it less easy for the parties to simply walk away”.

The Kenyan Private Sector Alliance (KEPSA), comprised of over 100,000 members, also played a role in mitigating election-related violence in Kenya in 2007-8 and 2013. Cooperating closely with civil society, KEPSA spearheaded a three-phased public communication campaign, ‘Mkenya Daima’ (meaning ‘My Kenya Forever’), garnering support for peaceful elections, as well as funding peace forums, preventing incitement, disseminating conciliation narratives, negotiating privately with political leaders, and organising presidential debates.

Related Articles

Sahel’s plight worsens amid fighting, says UN aid chief

03/18/2015. Conflict in Africa’s Sahel region is the biggest threat to saving lives in one of the poorest places on earth, according to the UN aid chief in charge there.

Launch: European Medical Corps

02/15/2016. To improve the EU’s preparedness and response to health emergencies, the EU has set up a European Medical Corps.

Hope for Palmyra’s Future

04/04/2016. After Islamic State retreated last month, a plan to rebuild an ancient city