There Are No Real ‘Safe Zones’ and There Never Have Been

Article published on Foreign Policy website on 03/30/2017 by Lauren Wolfe

As you climb the mountains high above Srebrenica, in the far east of Bosnia-Herzegovina, oak and beech trees become mixed with firs, pines, and spruce. It was into this green that Fatima Dautbasic-Klempic ascended in July 1995, fleeing massacres below.

“When we were walking through the mountains, we didn’t know who was alive, dead, or captured, or what happened to anybody,” Dautbasic-Klempic later told a British charity called Remembering Srebrenica. She recalled “dead everywhere, parts of bodies, blood on the buildings around us on the road — everywhere.” Below, 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys were being slaughtered that week. Women and girls, while usually spared death, were often raped. And all of this was happening under the watch of a United Nations Protection Force in a so-called safe area.

Srebrenica was one of six such safe areas set up in Bosnia in 1993. From the very beginning, Balkans experts described the plan as a “mockery,” pointing out that the zones would be like prison camps for refugees, easily starved out as food became undeliverable. These were places overcrowded with unarmed civilians, who would be sitting ducks without more protection from U.N. troops, critics worried. “It sounds good — ‘safe areas,’” an American military officer serving in NATO told the New York Times that October. Yet he explained that the peacekeepers “were little more than observers” without enough firepower. “The truth is the safe areas were always a myth.”

By the time of the Srebrenica massacre in the summer of 1995, there were only 400 “lightly armed and poorly supplied” Dutch peacekeepers protecting the city.

Originally, U.N. Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali had requested 37,000 peacekeepers from member states to protect Bosnia’s safe areas, but that was quickly revised toward a “light option” of only 7,600 peacekeepers after Security Council criticism, journalist David Rohde reported. The scant force left in the end did little to stop the killing, by all accounts.

This was not the first time “safe areas” — “safe zones,” “protected areas,” “humanitarian corridors,” “safe havens,” or any other euphemism for protecting civilians in war — would be used. There was Iraq in 1991, and Rwanda in 1994, as well as a few others. Yet none of these areas have been a success, experts say. Still, we are now faced with the idea of yet again creating safe areas, this time in Syria, as the Trump administration begins touting the idea ever more aggressively.

In January, President Donald Trump said he would “absolutely do safe zones in Syria,” which some have deemed a handy way of keeping more refugees out of the United States (i.e., if Syrians are now “safe” within their own country, they don’t need to come here). Then, on March 22, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said the United States would set up “interim zones of stability” in Syria.

Chris Boian, a spokesman for the U.N. Refugee Agency (UNHCR), said of Syria that “it’s an extremely, extremely fragile situation on the ground. It’s not easy to see how a safe zone solution could be applied there.” The creation of such an area would require basic services — water, food, sanitation, health care — that have all been pulverized in the war. While Boian is clear that UNCHR is interested in any plan that would save refugees’ lives, he points out that situations in conflict zones can be “very fluid.” The facts on the ground can change in the blink of an eye.

“In a very short space of time, those designated safe areas can become very unsafe,” he said.

Syria is a place in which the rules of war have seemingly been suspended. Red Cross vehicles, hospitals, and journalists have all been targeted. It’s hard to imagine how one would go about creating an untouchable zone for refugees within the country. If the Syrian government refuses to authorize such an area, there would need to be a U.N. Security Council resolution to authorize it — meaning Russia and China would have to agree to it, something U.N. players have basically shot down. “The complexity of the situation in Syria makes it very difficult to have an area that is absolutely safe for our purposes,” then-UNHCR head (and now U.N. secretary-general) António Guterres said in September 2015.

“There seems to be some sort of magical, wishful thinking at work here,” said Bill Frelick, the director of the refugee rights program at Human Rights Watch. “It comes across as an idea that Trump’s given seemingly no thought to whatsoever, and as with so many of his statements, it’s now thrown to his lieutenants basically to figure out how to implement a half-cocked idea.”

Frelick is also mystified by the wording of Tillerson’s “interim zones of stability.” What would such a zone actually be? The phasing suggests “something less than safe,” he said. “‘Stability’ is not safety, and ‘interim’ suggests that this is a short-term proposition.” So why did Tillerson choose the word “stability” over “protection”? Stabilizing an area does not mean you’re necessarily providing food, water, etc.

Frelick’s experience with safe zones goes back to northern Iraq in 1991, at the end of the Gulf War. More than 1 million Kurds fled the persecution of Saddam Hussein to Iran, while 400,000 tried to enter Turkey but were stopped at the border. These Kurds were forced to remain inside an unstable Iraq within a new “safe zone.” The United States, France, and Britain sent in troops to help, and a no-fly zone was established. And while history proves that many lives were saved because of the effort, the entire concept is considered by many to be a failure, in that it prevented refugees from fleeing their country. What is known as “refoulement,” a concept defined by the 1951 United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, should have applied to the Kurds here: “No Contracting State shall expel or return (“refouler”) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” Meaning: No country should trap any persecuted human being within a dangerous country.

Protection, as in the case of Iraq, “can also be a barrier from allowing people to get out when they need to,” Boian said. So all in all, the safe zone of northern Iraq receives mixed reviews.

Frelick was on the front lines of the Bosnian war and witnessed the failure of the safe areas there personally. The Dutch troops were present to protect humanitarian aid workers bringing in aid, he said. “When push came to shove, they stood aside and let people get murdered. This is why you need robust rules of engagement.”

A couple of months into Rwanda’s three-month genocide in 1994, when the worst of the killing was already over, the French pushed for the creation of safe areas through the U.N. Security Council. Known as Operation Turquoise, troops cordoned off one-fifth of the tiny country in the southwest to function as a safe zone. This part of the country was still under Hutu control, however, and in 2007, a commission set up to examine France’s role in the genocide found that the Hutu Interahamwe was able to operate freely within the zone, continuing its reign of terror against Tutsis. The Guardian reported that year that Gen. Jean-Claude Lafourcade, commander of Operation Turquoise, “admitted that the safe zone was intended to keep alive the Hutu government in the hope that it would deny the [Rwandan Patriotic Front] total victory and international recognition as the rulers of Rwanda. It was also an opportunity for France to help leading members of the regime to flee.”

In the case of Rwanda, safe areas gave shelter and food to civilians, but not protection.

Since then, a safe zone was set up in 2009 in Sri Lanka. There, 50,000 people were trapped while mortar rounds continued to fall and kill civilians and combatants. In February 2014, the European Union created a military operation meant to achieve a “safe and secure environment in the Bangui area” of the Central African Republic.” Violence continued sporadically over the year in which the soldiers patrolled. Before any of this, safe zones were established during the Vietnam War with little success. The areas were called “protected villages.” Apparently, according to Frelick, the joke there was: “We had to destroy the village in order to protect it.”

Experts seem to agree that safe areas cannot work, whether because they trap refugees who have the right to flee from moving, or because they are unable to prevent further violence within an active war zone. Their very premise, if you think about it, is questionable, Frelick said. Under humanitarian law, civilians are protected. “The idea that you’re safe on this side of the line, but unsafe on the other side of the line, is extremely problematic in terms of international humanitarian law,” he said. “It’s kind of nonsensical. There’s a kind of illogic to it.”

The only logical answer, then, to helping those trapped within a war zone is to actually bring about peace.

Related Articles

Edited highlights of the BBC interview with Mark Zuckerberg

02/16/2017. Mark Zuckerberg spoke with the BBC about his open letter on issues facing Facebook and society.

The continuing tragedy of Egypt’s Coptic Christians

05/30/2017. In the face of persecution and attacks for their faith, the Copts, who have persisted with their Christian faith in Egypt for the past 2,000 years, are making a statement by changing the chant.

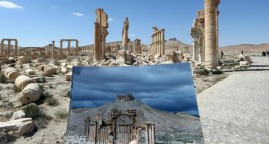

Conference on Safeguarding Endangered Cultural Heritage

12/03/2016. That visit provided an opportunity to begin the reconstruction and restoration process of the Timbuktu mausoleums, but also to begin international discussions.