When disaster strikes, should China do more?

Sixty-two Chinese rescuers and six sniffer dogs were the first global team on the ground in Nepal the day after a massive earthquake devastated the country just over a year ago.

The quick deployment was a sign of China’s growing role in emergencies, but critics say its humanitarian contributions are still paltry compared to its economic and diplomatic clout. With the world’s second-largest economy and largest standing army, China’s contributions do not match official pronouncements about its growing international role.

“We are trying to play a bigger role in the existing international order,” Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said at a press conference in March. The world is so big and faces so many problems; the international community wishes to hear China’s voices and see China’s solutions, and China cannot be absent,” he told reporters.

But the figures belie such statements.

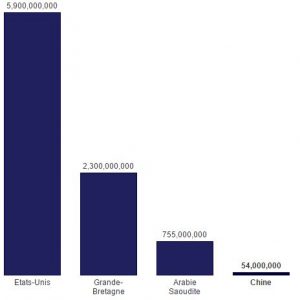

China contributed only $54 million in humanitarian aid in 2014, according to Development Initiatives, which analysed data from sources including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the UN, and the International Monetary Fund. In contrast, the United States contributed $5.9 billion, while Britain gave $2.3 billion, and Saudi Arabia $755 million.

The UN’s Financial Tracking Service, which documents global humanitarian aid flows, shows that China’s contribution fell in 2015 to a mere $37 million.

(The above figures are for humanitarian aid only, and do not include grants and loans aimed at development goals.)

Even China’s own statistics underscore the relatively low importance it places on foreign aid.

According to a 2014 white paper on foreign aid – including development as well as humanitarian funding – China’s average ratio of aid budget to gross national income was about 0.07 percent in the period from 2010 to 2012.

That’s much lower than the average 0.3 percent given annually by the 29 countries making up the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee, which include the Group of 7 advanced economies as well as smaller countries including Slovenia, Greece, and the Czech Republic.

In a recent commentary, the UK-based Overseas Development Institute said: “With greater power comes greater responsibility and China should step up its contributions to international humanitarian assistance to an amount at least remotely worthy of its GDP.”

The Ministry of Commerce, which administers Beijing’s humanitarian aid, has not responded to IRIN’s requests for comment and further information.

China: Superpower, humanitarian aid minnow

2014 humanitarian aid spending (US$m)

Politically motivated?

Observers have also noted that China’s aid often seems motivated at least in part by political goals.

“In terms of commitments overseas, it seems highly tactical,” said Kerry Brown, professor of Chinese studies and director of the Lau China Institute at King’s College, London.

He cited South Sudan, which gained independence in 2011 from Sudan, a long-time Chinese ally. China suddenly found itself in the awkward position of having invested heavily in oilfields that were now part of an independent South Sudan, while having provided support to the Khartoum government throughout the war, including supplying weapons.

China sent peacekeepers to join the UN mission in South Sudan, and contributed other humanitarian aid.

“We also saw this in Costa Rica in 2007 when China agreed to buy $300 million in bonds and give $130 million in aid to secure Costa Rica’s diplomatic recognition of Beijing instead of Taipei,” Brown said.

Learning curve

Some experts say it will take time for China to build up its humanitarian activities overseas. But as one of the most natural disaster-stricken countries in the world, China has the potential to contribute its considerable experience to disaster relief.

For example, when the worst earthquake in 30 years struck southwestern Sichuan Province in 2008, international agencies played only a small role and China’s response was widely praised. The government immediately launched a massive effort, which included deploying troops to rescue people buried in rubble, deliver aid and organise evacuations.

But critics also point out that China’s “draconian laws” stymie independent humanitarian efforts from Chinese NGOs.

“China might be a great power now, but it has to learn how to behave like one, especially in the area of humanitarian aid,” said Xu Guoqi, professor of Chinese history and international relations at the University of Hong Kong.

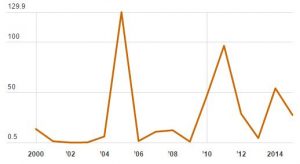

Humanitarian aid funding from China

(inflation-adjusted US$m)

Xu said China has very few NGOs relative to its population, and they are still figuring out how to function within China as well as abroad.

A former Chinese NGO worker, who requested anonymity and whose organisation recently shut down after losing access to international donors, told IRIN: “Many Chinese NGOs have relied on foreign funding, as local philanthropy is still underdeveloped. Now that the government is clamping down harder on civil society, NGOs are thinking about how to survive, not how to expand overseas.”

Inequality undermines charity

Despite rapid economic growth, private donations have not yet taken off.

“Even with so many newly rich people, charity-giving is still not widely spread as in many Western countries,” said Xu.

On Weibo, a popular Chinese website similar to Twitter, most discussions of China’s humanitarian aid are critical of the leadership for giving money to other countries when commenters felt the funds should be used assisting its own citizens.

China’s income inequality is among the world’s worst. The country’s Gini coefficient for income was 0.49 in 2012, according to a recent Peking University report, where a number above 0.40 represents severe income inequality.

“Some members of the public will think, ‘there are so many poor areas of China – why should [Chinese] give foreign aid?’ But this is changing,” a staff member of the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation told IRIN.

Since 2003, this Beijing-based NGO, which enjoys government support, has carried out disaster relief operations in countries including Indonesia, Haiti, the US, Myanmar, Nepal, and Ecuador with expenditure totaling around $13.7 million.

The CFPA staffer said the idea of charity could be catching on, judging by recent fundraising efforts.

“For example, many individuals gave contributions of more than 1,000 yuan ($150) for Nepal earthquake relief, and within 24 hours of fundraising to fight against the Ebola virus we raised 1.21 million yuan ($182,747) from the public,” she said.

Read the full article on Irin website

Related Articles

The Impact of COVID-19 on Humanitarian Crises

03/19/2020. The increasing spread of COVID-19 has dominated global attention. Governments and media are focusing attention on the domestic impacts of the virus and the medical and political responses.

Syria Changed the World

04/21/2017. The world seems awash in chaos and uncertainty, perhaps more so than at any point since the end of the Cold War.

Sweating the small stuff at the World Humanitarian Summit

05/26/2016. Meetings can seem a long way removed from the day-to-day challenges facing many in the aid world.