Local aid agencies: still waiting for a bigger share of the funding cake

Article published on 03/27/2017 on Irin Website by Louise Redvers

Donors and UN agencies who agreed to provide at least one quarter of humanitarian aid funding “as directly as possible” to local NGOs are struggling to deliver on their pledge.

Nearly one year after the commitment made at the World Humanitarian Summit in May 2016, signatories of the so-called Grand Bargain, a package of reforms to emergency aid delivery and financing, have yet to agree on three key points: the definition of “local”, what should be counted in the 25 percent, and how direct is “directly”.

The target is a response to the recognition that a small handful of large UN agencies and international NGOs receive the lion’s share of all international humanitarian funding, leaving local agencies feeling misused, unfairly exposed to risk, and unable to mature institutionally.

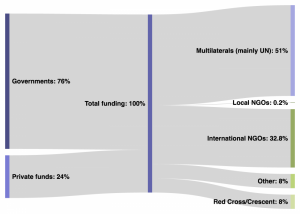

Local and national NGOs get, according to some calculations, as little as as 0.2 percent of direct overall spending, although they are sub-contracted by the larger aid agencies for much of the frontline implementation. One study, for example, found that Syrian NGOs were handling 75 percent of programme implementation, despite getting less than one percent of direct funding.

Advocates insist “localisation” will deliver more appropriate, cost-efficient, and accountable aid. The Grand Bargain agreement says it should both “improve outcomes for affected people and reduce transactional costs”.

Politics

Putting the pledge into action is facing strong practical and political headwinds, according to some 20 interviews IRIN conducted with signatory agencies, analysts, and practitioners.

On the practical side, donor government bureaucracies can’t suddenly allocate billions of dollars of new grants to small civic groups around the world.

Not only is there more donor work involved with writing a larger number of smaller cheques, but there is also greater risk associated with dealing with smaller, lesser-known organisations that might not always conform to international expectations around compliance and reporting.

At a time when political space is shrinking and populist politicians and media are increasingly sceptical about aid, it’s unlikely governments are going to become less risk-averse.

And, coming to the politics, those who now dominate the so-called “market” may not want to let go so easily.

Jemilah Mahmood, under secretary general for partnerships at the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), said it was only natural some international organisations “feel threatened by the localisation agenda” because it represents a potential reduction to their funding and role.

“There’s a lot of this that is kind of turning the system on its head… and it is quite challenging for us,” admitted Gareth Price-Jones, senior humanitarian policy and advocacy coordinator at CARE International.

He told IRIN it wasn’t a case of “downsizing” but of adapting to a different way of working. “A long-term culture change” is under way within his organisation, he said, citing the fact that CARE now holds discussions with local organisations at the programme planning stage, rather than just designing a project and then seeking local implementers to deliver it.

What’s local? What’s direct?

So how do you measure local aid funding and how do you define a ”‘local actor”? Can local affiliates of international NGOs be deemed local? What about national Red Cross or Red Crescent societies or local governments? Will assistance in-kind (bulk food aid, for example) or capacity strengthening count towards the 25 percent? And how many layers are allowed within the definition of providing funds “as directly as possible”?

These are some of the questions holding up progress towards the commitment.

“I am very concerned about the whole definition of localisation,” Degan Ali, executive director of Kenya-based NGO Adeso, and a vocal advocate for more direct funding for Southern NGOs, told IRIN. “There’s a lot of effort to try to dilute the language and the specificity of the targets.”

Anne Street, a leading voice within the Charter for Change alliance of international NGOs, which campaigns for more funding for local NGOs, acknowledged that definitions are a “sticking point” and “hugely political”.

“The first thing we need to do is define what is included in the 25 percent,” she explained. “Does it include capacity building, (secondments, training, etc); does it include food aid and materials?”

By tweaking definitions and including various sub-contracting arrangements, the proportion of funds spent through local NGOs can appear to increase dramatically.

This graphic, based on 2014 data from Development Initiatives, published in 2016, shows where humanitarian aid funding comes from and where it goes directly. Local charities and NGOs in affected countries get only 0.2 percent of direct grants from donors.

Street, also head of humanitarian policy at Catholic aid agency CAFOD, said that in some cases donors and agencies were trying to “position themselves to show that they are already almost reaching the 25 percent target”.

Any massaging of the numbers is “depressing,” she said, “because the objective was not to show you’re already doing it, but to do things differently in order to enable more effective and efficient humanitarian response, which is more locally-led.”

Consultations are under way on a relatively strict definition of what counts as local, one that excludes local affiliates of international NGOs (see box), and the findings of a survey conducted by aid consultancy Development Initiatives are due to be fed back to the Grand Bargain process before its annual meeting in June.

The categorisation is a first step towards better tracking of “local” funding flows.

The UN’s Financial Tracking Service and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development are ready to begin highlighting local and non-local breakdowns in funding data, but this requires that consensus on definitions. The harder problem will be to track indirect funding to local actors. For that, stakeholders say, operational agencies signed up to the Grand Bargain would need to report in much greater detail their sub-contracting arrangements, which so far are not public nor configured to illustrate localisation.

The Grand Bargain, meanwhile, has committed to develop a so-called “localisation marker” in conjunction with the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), the supreme body for coordination of humanitarian assistance.

However, some question whether this is the best approach. “A policy marker in general is designed to drive changes in policy and practice behaviour. It is not designed as an actual tracking tool,” one observer told IRIN.

Provisional categories of local humanitarian actors

- National NGOs/civil society organisations (CSOs): National NGOs/CSOs operating in the aid recipient country in which they are headquartered, working in multiple sub-national regions, and not affiliated to an international NGO.

- Local NGOs/CSOs: Local NGOs/CSOs operating in a specific, geographically defined, sub-national area of an aid recipient country, without affiliation to either a national or international NGO/CSO. This category can also include community-based organisations and faith-based organisations.

- Red Cross/Red Crescent National Societies: National Societies that are based in and operating within their own aid recipient countries.

- National governments: National governments/authorities in aid recipient countries e.g. National Disaster Management Agencies (NDMAs).

- Local governments: Local state actors in aid recipient countries e.g. local/municipal authorities.

- Local and national private sector organisations: Organisations run by private individuals or groups, usually as a means of enterprise for profit, that are based in and operating within their own aid recipient countries.

Source: Development Initiatives

The debates are testing the patience of some.

Olivier Bangerter, deputy head of multilateral affairs at the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, told IRIN the focus on the 25 percent “illustrates a fundamental misunderstanding” of what the Grand Bargain says.

“It all boils down to what is ‘as directly as possible’, and I think none of the signatories understood it as ‘directly’,” he said. For Bangerter, whose government is co-convening the Grand Bargain work stream on localisation with the IFRC, the focus should be on reducing transaction costs by decreasing layers.

To pool or not to pool?

A further point of contention is whether donors can count indirect contributions via pooled funds towards the 25 percent target.

According to Cyprien Fabre, a humanitarian policy advisor at OECD, “most people” agree that contributions to pooled funds can count towards the 25 percent target, because local agencies are usually among the beneficiaries.

But he also highlighted one of the central challenges inherent in the localisation agenda: Giving to local actors creates additional risk and cost for donors. “Individual donors don’t have the staff or grant-making capacity to take decisions at HQ level about local actors in particular contexts,” he explained.

Last year, pooled funds in 17 countries managed by the UN’s emergency aid coordination body, OCHA, channelled about 18 percent of their spending, or $129 million, to local NGOs and national Red Cross or Red Crescent societies.

But Ali, at Adeso, doesn’t believe contributions via UN-managed pooled funds should count. “If you allow the 25 percent target to go through a UN agency, then what is changing?” she asked. “In this case, well let’s not then have a 25 percent target, and say out loud that we want to keep the status quo.”

Mahmood warned against allowing pooled funding to become another “layer”, saying: “We need to make sure that a significant proportion of the fund does indeed go to local and national actors.”

Various mapping exercises are seeking to assess the different types of pooled funds and their impacts.

NEAR, a newly-formed network of Southern NGOs founded by Ali, is developing models for national pooled funds that would work outside UN agencies, prioritising local actors.

“We understand the limitations donors have with capacity and that they can’t write small cheques to lots of partners,” Ali said. “So why don’t we try a new type of fund managed by national partners that can write smaller cheques?”

In a parallel development, the UK’s Department for International Development is setting up a pilot fund with the Start Network for local and international NGOs in Bangladesh.

Representation

Amid all these tussles over tools and definitions, critics also argue that the discussion has been too “Northern-led” and has failed to include enough of the Southern actors it is supposed to be representing, not least the governments of affected countries.

“The whole process has been very exclusive,” one aid consultant familiar with the process told IRIN. “The whole idea about shifting the power dynamic in the system has not been reflected in any way in the commitments or in people’s behaviour.”

Sudhanshu S. Singh, chief executive officer of Humanitarian Aid International, an Indian NGO platform, bemoaned the lack of interaction with local organisations, although he praised a recent workshop held in Geneva by Switzerland and the IFRC – to which a number of non-signatory and southern representatives were invited.

“Frontline organisations and grassroots [groups] still don’t know what [the] Grand Bargain is all about,” he said. And while he believed many donors were genuinely committed to the 25 percent target, he called for more awareness among local organisations so that they could “exercise their entitlement”.

Federated NGOs

Singh also expressed concerns about international NGOs registering within countries in the Global South – not only counting these as conduits for “local” funding, but also collecting money domestically under their global brands.

“So, on one hand, they talk about empowering local organisations and giving 25 percent to them as directly as possible, but, on the other hand, international organisations are encroaching upon fundraising space in growing economies and developing countries,” he said.

Julian Srodecki of World Vision, which has set up local branches, defended the practice, saying: “What’s local and what’s not varies by context.”

He gave the example of World Vision India having been based in India longer than World Vision UK had been in the UK. “Does that mean World Vision UK cannot legitimately fundraise within the UK, because 50 years ago they were not based there?

“I fully support the idea of empowerment in the [Global] South,” he continued. “But… at the end of the day, I think what should count is the performance outcomes for the affected people.”

Slicing the cake?

Bangerter, from the Swiss government, agreed. “It is sadly a point often forgotten in the discussions: [Localisation] is not about giving money away from internationals to locals, but about using the money in a more efficient way, for the sake of those we claim to serve.”

He added: “It is not about which humanitarian actor receives which slice of the cake, but about how many people you can feed with the cake, literally.”

In February, the IFRC carried out a mapping exercise to collate ongoing initiatives aimed at improving funding for local and national actors.

The report, shared with members of the localisation work stream this month, contained more than 40 examples of global projects around capacity building, pooled funds, networks, training, and evidence collection.

Nonetheless, few interviewees believed the 25 percent target was achievable by 2020, and some even suggested the target – and the focus on definitions – was a distraction.

“Let’s just get on with it,” one work stream member said. “We should be looking at countries where localisation can be strengthened and where international response doesn’t have to take place, and build on that.”

For Mahmood of IFRC, “trying to get change to happen overnight is not going to be easy.” But she added: “I am optimistic; it is an idea and a wish whose time has come and it’s up to us to turn it around to a reality that is sustainable.”

Related Articles

How America Receives Refugees

02/20/2017. “We Were So Beloved” is Manfred Kirchheimer’s personal documentary about the German Jews who made it to the United States—and those who didn’t.

Mandate for ICRC’s President extended for third term

11/29/2019. Peter Maurer will serve a third mandate as president of the International Committee of the Red Cross following a vote by the ICRC’s governing body, the Assembly, on 28 November 2019.

New Vatican emphasis on ‘20 action points’ for migrants, refugees

11/08/2017. In recent days, Pope Francis and a Vatican official have cited “Responding to Migrants and Refugees: Twenty Action Points”