A Study on the Roots of Restraint in War

Article published on ICRC website on 03/15/2017

The Roots of restraint in war is a two-year research initiative launched by the ICRC to advance its understanding of how norms of restraint develop and spread through State armed forces and non-State armed groups.

Nine academics will investigate sources of influence on the behaviour of combatants in eight armed groups, and explore cases of community self-protection. The findings, implications and recommendations of the research will be published in 2018.

Background

In 2004, the ICRC published a study The Roots of Behaviour in War2 that identified key factors that influence the behaviour of combatants in armed conflicts. The study paid particular attention to the psycho-social processes that condition individuals to either act in accordance with, or to violate, norms of international humanitarian law (IHL).

When analysing reasons why IHL violations occur, the study’s findings echoed observations made in several scholarly disciplines that emphasized the role of group conformity3 and of obedience to authority4 in contributing to a moral disengagement5 of responsibility for one’s acts: individual preferences are ceded to group preferences in the former, and to a superior authority in the latter. In a parallel process, behaviour that violates moral standards is justified in the minds of perpetrators by a range of rationales including revenge for atrocities committed by the opposing side and a sense that a short war disregarding the rules is preferable to a protracted one that respects them.6 This process is amplified when the ‘enemies’ are depicted as inferior beings, labelled cockroaches or snakes in the case of Tutsis during the genocide in Rwanda.

The study made important recommendations for policy at the ICRC. First, the moral relativism observed among those affected by conflict led the authors to recommend that the ICRC approach the teaching of IHL as a legal and political issue and not as a moral one: to focus on legal norms rather than the values underpinning them since the latter were seen to shift according to the reasons for, and way in which, conflicts are fought. Second, in recognition of the importance of the peer group and hierarchical structure in conditioning behaviour, the authors suggested that rather than simply raising awareness of IHL, the ICRC should encourage armed forces to integrate IHL into their doctrine and training, and to establish sanctions for breaches of the law. In other words, persuade armed forces to make respect for IHL a clear command, assist in the development of training in applying the rules, and advise on the establishment of compliance mechanisms. The ICRC has pursued these policies over the last decade with both State and non-State armed actors: examples of the latter include the ICRC’s engagement with the Moro National Liberation Front in the Philippines, and the Justice and Equity Movement and Sudan Liberation Movement – Unity in Darfur.

An assumption underlying this approach to fostering respect for IHL is that armed groups have a vertical hierarchical structure through which doctrine and discipline can flow from the leadership to the rank-and-file. Yet much of the violence of the last decade has been carried out by armed groups that do not possess a centralized structure and chain of command. The emergence and proliferation of such groups has been a feature of many contemporary conflicts including those spawned by the 2011 ‘Arab Spring’, insurgencies in Iraq, Syria, Ukraine and Afghanistan, and among the self-proclaimed ‘jihadi groups’ in Africa, South Asia and the Middle East. By the end of the war in Libya, for example, there were 236 separate armed groups in the city of Misrata alone,8 and over 1,000 individual groups are thought to be fighting in Syria.9 Furthermore, the failure of State security forces to contain the threat posed by ‘jihadi’ groups like Boko Haram, has in turn prompted the formation of local community-defence groups bearing arms, further proliferating the number and types of armed groups present. The proliferation of non-State armed groups and governmentsponsored militias has serious ramifications for the safety of civilians.

New research

It is with this concern in mind that the ICRC decided to revisit the Roots of Behaviour in War study. Ten years on, what impact has incorporating the law in training and doctrine had on curbing violations of IHL? What aspects of the integration model have been most influential -the doctrine, the training or the compliance mechanisms? How do the formal norms created at the organizational level interact with informal norms at lower levels (platoon, group and unit)? Are there parallels between norm formations in these smaller groups with that of small armed groups operating without a central hierarchy? What are the sources of influence on the development of norms of restraint in these loose alliances of groups? And ultimately, how can the ICRC and other humanitarian organizations exert their influence on this process to foster better respect for civilians caught up in armed conflict?

The new study will address these core questions through an empirical analysis of eight armed forces/groups, plus a thematic study of community self-protection initiatives, conducted by leading scholars in the field of armed group behaviour. The focus will be on understanding how norms of restraint form within these different groups by identifying their sources of influence at several levels. The notion of restraint helps to narrow the scope of the study and provide focus for future policy. Most studies in this field either document specific forms of violence such as killing or rape, 10 or seek to identify patterns in “repertoires of violence”11 in order to understand why such violence occurs. Causal explanations for restraint have received less attention,12 yet potentially provide more policy-relevant insights for organizations like the ICRC that are trying to promote respect for humanitarian norms.

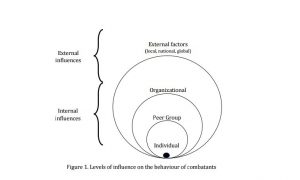

Research framework To better understand each type of armed group and make comparisons across groups, the

researchers distinguish between four different levels of influence on soldiers and fighters. This framework is derived from the “standard model” of military cohesion and recent research on the internal structures of non-State armed groups.

Levels of influence on the behaviour of combatants

1. Individual

Through structured and semi-structured interviews, the researchers aim to understand how the different types of influences shape an individual’s understanding of, and respect for, norms of restraint. Individuals might adhere to certain norms for a range of reasons, whether religious, cultural or personal. In keeping with the first study, the researchers will also revisit whether, in the different types of groups, there is a correlation between knowing the norms of IHL and respecting them.

2. Peer group

The researchers will examine how informal social norms form in peer groups and influence individual behaviour. Many of the informal social norms central to small-scale peer groups are not included in formal codes of conduct typical of State armed forces. For instance, courage and the idea that one should “never leave a fallen comrade behind” do not usually appear in a group’s formal code of conduct, but are central to the informal warrior creeds or

ethos of a group. The study will explore whether the size of a group matters for such norms to develop. It is important to understand the hierarchy of influences to see how and when norms are enforced: transgressions of norms may be punished by fellow members of the group through, for instance, beatings, social isolation or reprimands.

3. Organizational

A larger fighting force is usually bound together by an organisational identity14 derived from an exclusive organizational doctrine, codes of conduct, and rites of passage. 15 But in many non-State armed groups, organizational influence is absent. While some groups may have thousands of members and appear to operate as one group, they actually function as a loose alliance of autonomous sub-groups, each held together and influenced solely by the informal social norms of their peers. Hence the study will examine organizational influence in the eight groups and forces to ascertain when and how it impacts the behaviour of individuals and the formation of peer-group social norms. The study will pay particular attention to codes of conduct (both formal and informal) and the role they play in forming norms: how individuals learn the rules and their place in the group dynamic. This includes the formal and informal ways transgressions are punished within a group.

4. External factors

Typically, combatants are isolated or at least periodically displaced from the social networks they were a part of before joining the group. With the advent of social media and smartphones, combatants are no longer so isolated. This is obviously the case for seniorcommanders, who have more contact with people in the outside world than the rank and file. These people may be influential in determining individual behaviour. They include religious and spiritual leaders, local community notables, the media and international organizations. Hence the study will explore the relative importance of these external contacts and networks in influencing norms of restraint. Specific attention will be paid to how the media and public communication influences behaviour, and to negotiations between armed groups and humanitarian agencies over safe access to people in need of humanitarian assistance.

The study is coordinated by Dr Brian McQuinn, Dr Fiona Terry and Mr Benjamin Eckstein at the ICRC. It is overseen by an 8-member steering committee of senior ICRC staff and an Ethics Review Board. Field research will be completed in 2017 and a final report published in 2018.

Related Articles

The Impact of COVID-19 on Humanitarian Crises

03/19/2020. The increasing spread of COVID-19 has dominated global attention. Governments and media are focusing attention on the domestic impacts of the virus and the medical and political responses.

Pope Francis receives the Grand Master in Audience: “Go ahead with courage, you express spirituality through your works”

06/22/2018. During the meeting, the Grand Master illustrated the Order of Malta’s main activities in the humanitarian and diplomatic sectors last year.

How to better fight human trafficking: The Order of Malta organizes conference with international experts to forge new synergies

10/09/2019. The Order of Malta organizes conference with international experts to forge new synergies