Time to Reset African Union-European Union Relations

Article published on International Crisis Group website on september 2017

Relations between the African Union (AU) and European Union (EU) reached a nadir in 2016 following serious disagreements over European payments to AU peacekeepers in Somalia. The fifth AU-EU summit in November presents a chance to reinvigorate the partnership if both sides can deal openly with disagreements, address deep-seated mutual frustration and agree to tackle the root causes driving migrants toward Europe.

Executive Summary

African and European leaders are scheduled to meet in November for the fifth triennial African Union-European Union summit at a time when relations between the two institutions have reached a turning point. Both are in transition, undergoing internal reforms that will have serious implications for their future peace and security partnership. After significant disagreements in 2016 over European Union (EU) payments to troops in the African Union (AU) mission in Somalia, there is now considerable political will on both sides to strengthen cooperation. While collaboration has improved in some areas in recent months, deep-seated frustrations over financing and each other’s perceived deficiencies remain strong. Relations are too emotional, bound up in colonial history – a breeding ground for mistrust and resentment. If the relationship is to be deepened, both sides must deal openly with disagreements. Deliberations should be less transactional, moving away from a narrow list of African demands and negotiations over what the EU will pay for. Instead, they must be more strategic, based upon clearly articulated interests.

The AU has embarked on a potentially transformative process of institutional reform that, if implemented, will make it leaner and more efficient and should increase its financial self-sufficiency. However, there are significant challenges to the AU’s authority resulting from the changing nature of conflict in Africa, especially the spread of jihadist and other non-state armed groups, and the concomitant rise of ad hoc military coalitions to combat them, such as the Multinational Joint Task Force in the Lake Chad basin and the G5 Sahel. These changes also bring into question the suitability and sustainability of the continent’s peace and security architecture. Designed in the 2000s, it is now under strain and in need of wholesale review. The AU needs to clearly set out its strategic priorities and define its role in peace and security, deciding whether to focus on developing and harmonising policy and maintaining political oversight or becoming an implementer of projects. It also should reassess its relations with the regional economic communities, a central element of the continent’s security architecture, clarifying which organisations should take the lead in conflict situations.

With the prospect of the UK’s exit, the EU is preparing for life without one of its most influential and wealthy member states. This inevitably will impact its relations with the AU, as will renegotiation of the Cotonou Agreement, a partnership between the EU and 79 sub-Saharan Africa, Caribbean and Pacific countries which expires in 2020. The African Peace Facility, the main source of EU support for the AU’s peace and security activities, is funded through the agreement’s financial instrument, the European Development Fund.

The EU is one of the AU’s most significant peace and security partner; since 2004 it has provided more than €2 billion ($2.39 billion) in assistance. The question of financing is one of the areas of greatest tension between the two institutions. Their relationship is essentially that of donor and recipient but both are reluctant to characterise it as such, even though they actively, if inadvertently, perpetuate the dependency. The EU increasingly resents being treated like a “cash machine”, especially as it believes it does not receive due recognition. It wants the AU to pay its “fair share”. The AU claims to want this too. It wishes to reduce its reliance on external support and, as a result, member states have agreed to proposals for a 0.2 per cent levy on imports to the continent that could generate more than $1.2 billion per year. This is essential. If the suggested levy is not workable for some or all member states, alternative solutions must quickly be found.

The vexed donor-recipient dynamic is further complicated by tensions over the legacy of European colonisation, which intensified greatly during Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma’s tenure as AU Commission chairperson. This has a detrimental effect on trust and confidence, prevents free and frank discussions and bars progress toward an interest-based partnership.

The AU-EU summit is unlikely to be as transformational as the two institutions would wish – preparations have not progressed far enough for this. But it could still be a useful springboard for more strategic discussions and movement toward an interests-based relationship, if the following steps are implemented:

Pursue a pragmatic partnership based on mutual interests: assertions about an “equal partnership” in a seriously imbalanced relationship cause unnecessary tensions, irritating some AU member states and raising unachievable expectations. The notion, while remaining an aspiration, should be de-emphasised and replaced with a more pragmatic understanding of AU and EU mutual interests and the interdependent nature of their relations.

Focus on strategic and political interests: discussions of the minutiae of what the EU will or will not pay for tend to dominate AU-EU meetings at all levels. It will be hard to avoid financial matters, but the summit should focus on matters that are vital to the long-term interests of the two unions and address the issue of funding as part of a strategic examination of peace and security after Cotonou. Ideally, any future support should be predictable to enable the AU to do more medium-term planning, and flexible to permit adopting new initiatives and adapting the continental security architecture. It also should include an instrument for rapid reaction like the existing Early Response Mechanism. Support should focus on four key areas: early warning; preventive diplomacy and mediation; peace support operations; and capacity-building and non-lethal equipment for AU member states’ military and security forces. To encourage AU member states to increase their financial support, any future mechanism should be based on a matched funding system in which the EU’s contribution is proportionately linked to those made by African governments.

Put migration on the agenda: another step toward a more interests-based partnership would be the inclusion of migration and mobility on the summit agenda, a highly contentious issue that AU member states are reluctant to discuss openly. The EU’s kneejerk reaction to increasing flows of irregular migration from Africa has alienated the AU, which wants Europe to increase legal migration routes and tackle root causes rather than the seal its borders. However uncomfortable, the issue should be on the table – it will permeate the meeting regardless.

Addis Ababa/Brussels/Nairobi, 17 October 2017

Related Articles

The final desperate plan

03/21/2016. Every week, Jean-Marie Colombani, co founder and director of Slate.fr expressed freely and subjectively his views on the highlights news.

A Conversation With Nikki Haley

03/30/2017. The Ambassador discusses the United States’ goals for its term as president of the UN Security Council in April, and outlines her plans to highlight human rights and to assess current UN peacekeeping missions.

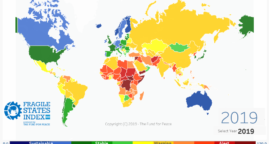

Tipping points 2019 | Lessons from fragility

04/10/2019. You can probably guess the country ranked “most fragile” on the 2019 Fragile States Index (FSI) produced by Fund for Peace, a Washington-based think tank.